Author: BD Joyce

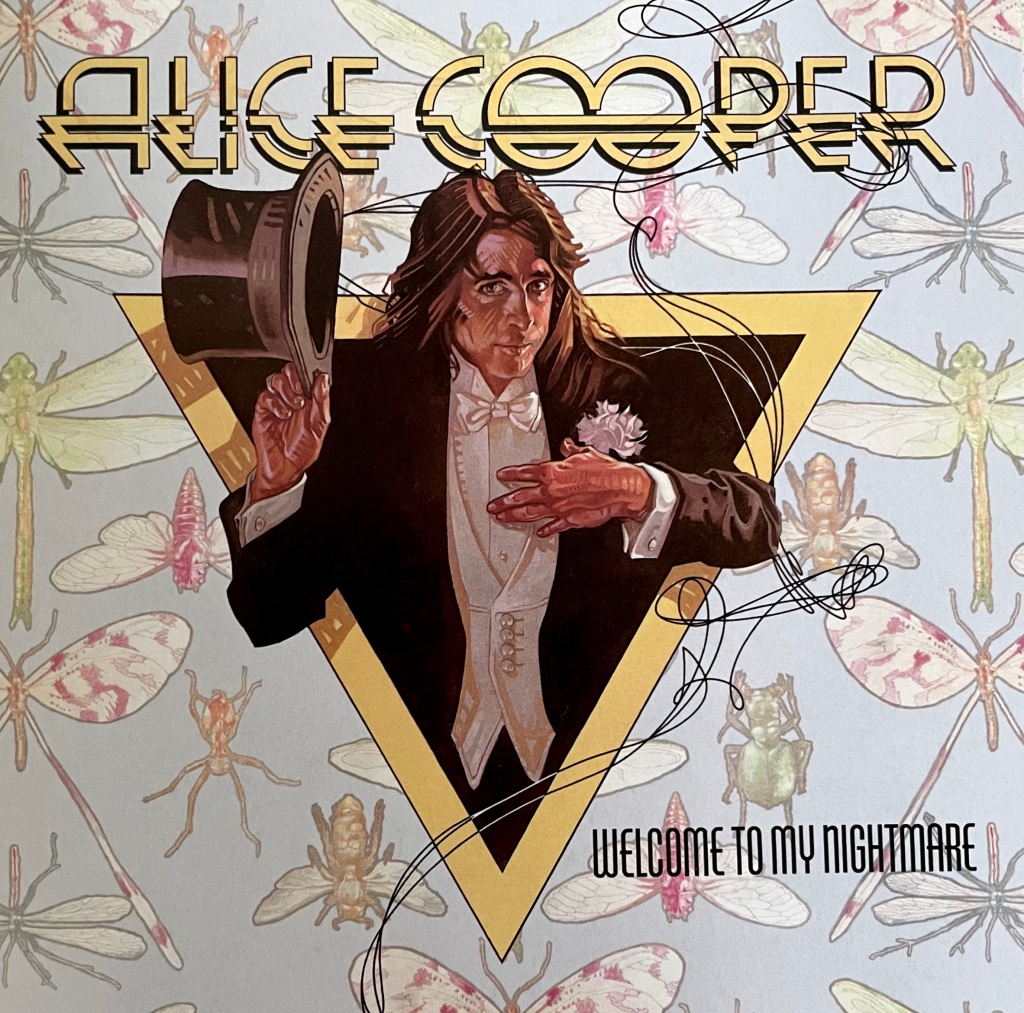

- Artist: Alice Cooper

- Album: Welcome To My Nightmare

- Year of Release: 1975

- Country: USA

- Label: Atlantic / Rhino

- Format: Jewelcase CD

- Catalogue Number: 8122-74383-2

Although ostensibly the eighth release under the Alice Cooper banner, Welcome To My Nightmare should in many ways be considered the debut album of Alice Cooper, former vocalist of Alice Cooper, the band. Prior to this album, Alice Cooper was very much a collective, a fully-functioning band, a gang of five friends who collaborated on their music, forging an almost telepathic musical link over more than a decade, a decade during which they released at least one stone-cold classic album, and a handful of good to great works which have stood the test of time in spectacular fashion. All good things, however, must come to an end, and 1973’s Muscle Of Love, while a long way from the disaster that it is occasionally portrayed as, was clear evidence of the waning powers of the group, and of the friction and disharmony that ultimately pulled the band apart. Indeed, the success of Welcome To My Nightmare became the final nail in the band’s coffin, the album’s huge sales and enormous popularity providing the affirmation that Cooper needed to strike out on his own in perpetuity. Or at least almost perpetuity. Happily, the late 1990s saw time do its healing work, resulting in a thawing of relations between the members of the original Alice Cooper line-up has seen them writing and performing together sporadically over the past twenty years, as Cooper has revisited the sound that propelled the band to their initial successes.

Understanding the circumstances of the dissolution of the original Alice Cooper is helpful in allowing the listener to accept the solo version of Alice Cooper as something of an inevitability, rather than an unexpected turn of events, and this softens the disappointment of the absence of Buxton, Bruce, Dunaway and Smith. Although they were far from a one-dimensional band, with a wide array of influences surfacing across seven albums, their best work had a white-hot, proto-punk intensity, borne out of the tough clubs and bars of the industrial cities of the American North-East, the same circuit that produced The Stooges, The MC5 and Ramones, all bands with a similar uncompromising spirit to Alice Cooper. The rough edges and free-wheeling fervour engendered by the band’s circumstances, adding the nurture to the band’s innate nature remains one of the most appealing components of the early Alice Cooper sound, and there is no doubt that right from the outset of Cooper’s solo career, that these edges were intentionally smoothed, with the emphasis shifting from the delivery of the songs to the composition itself. Although this is initially disheartening for a listener drawn to the unfettered sound of early Alice Cooper, the calibre of the songs themselves makes it difficult to avoid being converted to the cause, and once this happens, one can enjoy this magnificent album, unencumbered by the need to compare and contrast with the more underground charms of Love It To Death, or Killer.

Welcome To My Nightmare is much more than simply a magnificent set of songs, however. Although School’s Out had flirted with the idea in a slightly non-linear way, this time round, with the resources and cast of musicians available to translate his aspirations into reality, Cooper, rather in the vogue of the time, fully embraced the idea of the concept album. Ably assisted by the now in-demand Bob Ezrin, Cooper assembled a fine supporting cast borrowed mainly from Lou Reed’s band, including the excellent Dick Wagner and Steve Hunter on guitars, and Prakash John holding down the low end. It almost goes without saying that any bass player that spent time with George Clinton’s outstandingly funky Parliament / Funkadelic collective would be a worthy addition to any band, and he more than proves his worth here, his sparkling basslines a notable feature of many of the best tracks. As if that were not enough bass firepower, the legendary Tony Levin of King Crimson (and literally 500 albums released by artists as diverse as John Lennon, Carly Simon and Buddy Rich) pops up on the title track, and closer ‘Escape’. Pulling everything together is the much-sampled Vincent Price, probably the most recognisable voice in horror, narrating the journey through the nightmares of a child named ‘Steven’, also the name of one of the most memorable songs on an album almost overflowing with them.

The aforementioned title track is the perfect introduction to the new Alice Cooper sound. The slick, smooth funk wrongfoots a listener expecting an up-tempo and energetic start, but in fact the understated nature of the insidiously catchy song draws us in, almost imperceptibly, into Steven’s nightmares. The song is expertly-paced, and Cooper’s vocal is disquieting in its intimacy. In the gradual addition of the various layers of the track, from the fantastic texture of the steel-stringed acoustic guitars of the first part of the song, through to the subtle Steely Dan organs, and the clipped rhythms of the wah-enhanced electric guitars, the deliberate way in which the song is constructed to maximise the impact of each of the constituent elements is a masterclass in songcraft. A cinematic bridge section, which utilises a gorgeous string and horn arrangement adds depth and complexity to an already beguiling mix, and the descending horn figure that eventually develops is worthy of a Curtis Mayfield or Marvin Gaye hit, adding dripping layers of funk and soul, and setting the scene brilliantly for an album that at this point can go almost anywhere across the remaining tracks.

And while we’re not quite talking Zappa levels of eclecticism here, Welcome To My Nightmare is indeed a wide-ranging album that is uses a variety of moods and genres to tell its story. The shit-kicking rock ‘n’ roll that we are waiting for is provided by the joyful ‘Department Of Youth’ and the brilliant and slightly queasy tale of necrophilia that is ‘Cold Ethyl’, ”The Black Widow’ brings the camp, occult proto-metal, and ‘Some Folks’ sees a return to the kind of jazz hands brandishing, Broadway theatricality that the original band explored on School’s Out. And where the title track is the album in microcosm, displaying Cooper’s deft use of melody and arrangement to construct a progressive, but never less than memorable song, every one of the tracks named above contain moments of magic, fine details that are a testament to the world-class level of diligence, thought and love that has been poured into every second of the album. ‘Department Of Youth’ switches between an economic groove and the kind of half-time wall of sound that wouldn’t sound out of place on a Phil Spector production, before a triumphant coda which achieves the almost unheard of feat of successfully adding a children’s choir to a rock song, without it sounding trite and tacky. ‘Cold Ethyl’ is an irresistible Stones-meets-Kiss glam stomp that guarantees a good time from the first hit of the cowbell, and ‘The Black Widow’ combines delightfully fuzzy riffage, with stacked vocal harmonies and intricate instrumentation, before a marching band finale once again sees Cooper subverting classic Americana for his own devious ends. The cabaret of ‘Some Folks’, for all of the variety that it brings to proceedings, is one of the weaker tracks on the record, but even so, thrills with Prakash John’s phenomenal bass work, which offers a spiky contrast to the smooth sonics of the rest of the band, almost poking into the space left by the guitars and drums with delicious, syncopated runs.

The twin jewels in the album’s crown though, are the two ballads, very different in tone if not their musical quality. ‘Steven’, the main theme for the album’s protagonist, which features Cooper singing in first person at points, allowing us access to Steven’s internal monologue, is a return to the kind of creepy horror-rock that we have previously encountered on Killer and Love It To Death, in the form of ‘Dead Babies’ and ‘The Ballad Of Dwight Fry’. A true rock opera, in multiple parts, the track positions the listener firstly in a cold, eldritch room, the harpsichord lines adding a cinematic quality, before we venture into dusty corridors in search of deliverance, passing long-forgotten rooms, encountering snatches of strings and woodwind as we go, feeling our way through a shadow world. A twinkling piano melody, redolent of Mike Oldfield’s ‘Tubular Bells’, introduces the much more opulent, Grand Guignol climax, in which Cooper sings Steven’s name over and again, atop dramatic pianos and strings. The decision to eschew the temptation of smothering the conclusion to the song in crashing guitars, instead favouring sonorous piano chords, is expertly-judged, bringing a rich and solemn depth to a track that could so easily descend into the cliché that it avoids. ‘Only Women Bleed’ is even better, an utterly world class song that might be the best thing Cooper has ever put his name to. An almost country-sounding ballad, the track is perfectly conceived, and immaculately arranged and performed. Once again demonstrating Ezrin’s gift for clever use of classical instrumentation, the horns that accompany the gentle arpeggio that commences the song are sweet, but not cloying, reminiscent of a more restrained take on George Martin’s much-maligned work on The Beatles’ Let It Be. The star of the show here though, is Cooper’s sweeping vocal melody, which he delivers in an angelic tone that demonstrates that immense and sometimes under-utilised talent that lies at the heart of a sometimes under-appreciated vocalist. As Cooper intones the utterly gorgeous descending melody line that makes up the pre-chorus – ‘She cries alone at night too often / He smokes and drinks and doesn’t come home at all’ – he achieves a truly tear-jerking quality that we rarely find in the irreverent world in which Cooper operates, his voice thick with an emotion that appropriately reflects what seems to be the unironically weighty subject matter, lamenting the life of a battered woman, who is presumably Steven’s mother. Perhaps wary of dwelling for too long in this lugubrious space, an electric organ ushers in wonderfully atmospheric strings that in turn lead us to a majestic instrumental section where the guitars transport the listener to an altogether more blissful state, the light at the end of the tunnel. A light that the final track, ‘Escape’ makes concrete. The song itself is a serviceable cover of a rather obscure single by The Hollywood Stars, but it is chosen surely for it’s subject matter, and carefree bubblegum pop feel. It’s not the best thing on the album, but it is undoubtedly thematically important in the way that it completes Steven’s story.

The sense of completeness is the overriding feeling that one is left with, once the final notes of Welcome To My Nightmare fade. After a partially self-inflicted period in the doldrums during the early 1980s, Cooper ultimately returned to huge commercial success later in that same decade, but although the likes of Constrictor and Trash are strong works, they do not quite capture the magic of his very first solo album, which is simply a perfect storm of sharp and unforgettable songs, played by great musicians performing at the top of their game, all in service of a unifying concept which allows a varied set of songs to hang together so effectively. It may not quite best Billion Dollar Babies, the high watermark of the original Alice Cooper quintet, but for the man himself, it represents the second of a pair of twin peaks that cement his monumental contribution to rock ‘n’ roll forevermore.